Allegheny Observatory of the University of Pittsburgh

Historical Highlights

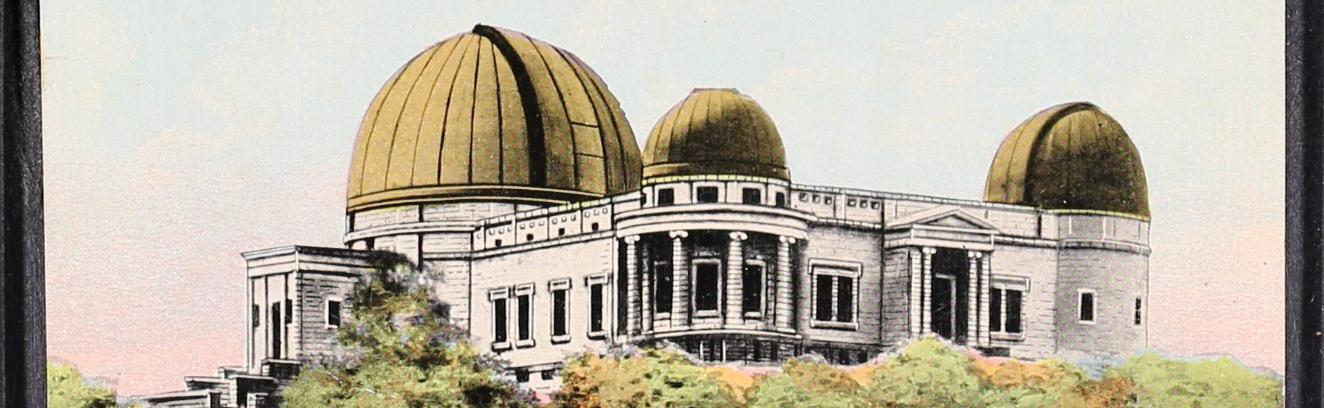

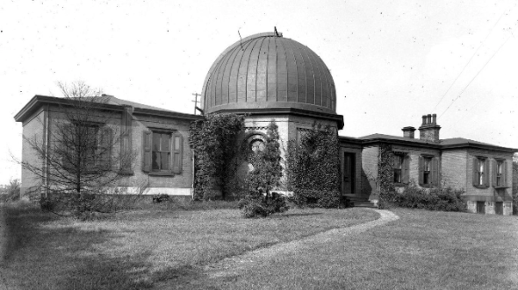

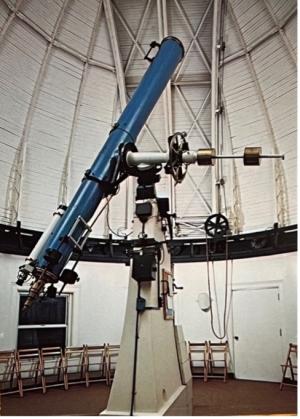

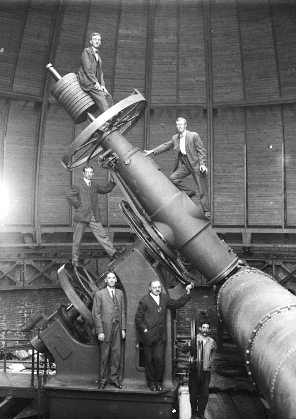

Founded in 1859, University of Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Observatory (AO) is among America’s earliest astronomical institutions. AO is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, has a Pennsylvania state historic marker, and is a Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation Historic Landmark. The original single-domed building (Figure 1) was replaced with a new 3-domed building (Figure 2). Construction of the new Observatory began in 1900, and the building was dedicated in 1912. Still in operation are the 13-inch Fitz-Clark Refractor from 1861 (Figure 3) and the 30-inch Thaw Refractor from 1914 (Figure 4). Back in 1861 the Fitz-Clark Refractor was the 3rd largest telescope in the world, and in 1914 the Thaw Refractor was, and remains, the 3rd largest refractor in the United States.

History

Starting in the 1860s, the institution of Allegheny Observatory began making outstanding contributions to the physics enterprise across diverse domains including basic research, instrumentation, invention, and societal benefit. Using available telescopes at Allegheny Observatory, the physics and astronomy contributions of its earliest Directors in the late 19th and early 20th century were both significant and historic. To this day Allegheny Observatory remains an important site for educating students, fostering undergraduate research experiences, and conducting education and outreach programs accessible to K-12 students and the public.

Pre-1900 Contributions at the Allegheny Observatory

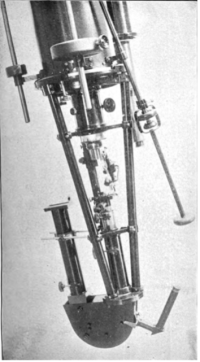

History of the 13-inch Fitz (now Fitz-Clark) Refractor. The original 13-inch lens with a focal ratio of f/14 was made by Henry Fitz, but it was stolen and held for ransom in 1872. After refusing to pay the ransom, the lens was found a few months later but the lens was badly scratched. The scratch was removed, and the lens was superbly repolished and refigured by the famous optician Alvan Clark; hence it is now known as the Fitz-Clark Refractor. Most notably, and as described below, this telescope played a major role in Langley’s solar research and Keeler’s research on the nature of Saturn’s rings.

Samuel Pierpont Langley was the first Director of the Allegheny Observatory from 1867 to 1891, upon its donation to the Western University of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pittsburgh) by a group of private citizens. Langley eventually became the 3rd Secretary of the Smithsonian in 1887 but remined affiliated with the Allegheny Observatory after that time and founded the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in 1891.

Samuel Pierpont Langley was the first Director of the Allegheny Observatory from 1867 to 1891, upon its donation to the Western University of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pittsburgh) by a group of private citizens. Langley eventually became the 3rd Secretary of the Smithsonian in 1887 but remined affiliated with the Allegheny Observatory after that time and founded the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in 1891.

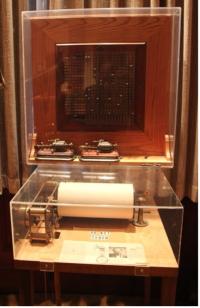

Beginning in 1869 Langley measured stars transiting the meridian to devise the first precise time standard called the Allegheny Time System. From 1869 to 1883, Allegheny Observatory broadcast time over more than 4,700 miles of telegraph to cities and railroads in the US and Canada, marking the first systematic distribution of precise time. This places Allegheny Observatory at the vanguard of using physics and astronomy to deliver a unique, immense societal benefit. His transit telescope, clocks, and telegraph are still on display at the Allegheny Observatory. The need for the service that Langley established became so great that the US Naval Observatory began providing the signals using taxpayer funding in 1883. Langley’s work with time distribution and railroads was integral to the national establishment of standard time and time zones years later. In 1883 all railroad companies in North America adopted four time zones and began operating on standard time. In 1918 the US Congress officially adopted standard time, as explained in the Heinz History Center (https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/blog/western-pennsylvania-history-samuel-langley-pioneering-standard-time/).

Langley’s early scientific interest was the physics of the Sun, and his many accomplishments include his pioneering work on measurements of the solar constant and the infrared portion of the solar spectrum. He is also known for his magnificent sunspot drawings. Langley invented the Bolometer at Allegheny Observatory in 1878.

His bolometer was based on the principle that the electrical resistivity of certain metals is a sensitive function of temperature. By 1880, he perfected the design of his bolometer so that it could “detect thermal radiation from a cow a quarter of a mile away”. Using his bolometer Langley discovered new infrared atomic and molecular absorption lines, measured the strong variation with wavelength of Earth’s atmospheric absorption, and made the first accurate calculation of the solar constant. These results were later used by Svante Arrhenius (1903 Nobel Prize in Chemistry) in 1890 to demonstrate the greenhouse effect; Arrhenius explained that increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, primarily from human activities like burning fossil fuels, could significantly raise the Earth’s temperature through the greenhouse effect and lead to climate change. Bolometers are now essential physics instruments with applications extended to astronomy, particle physics, plasma physics, and thermal cameras. For example, bolometers are now used to measure and map the intensity and temperature fluctuations in the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation across the sky to better than one part in 100,000. The CMB is a smooth afterglow throughout the sky emitted when the Universe was only 400,000 years old, well before stars and galaxies existed. The discovery of the CMB in the 1960s was a key finding to support the Big Bang Theory of the origin of the Universe. Several Nobel Prizes in Physics have been awarded for studies of the CMB.

Langley began Experiments in Aerodynamics at Allegheny Observatory in 1886. On the grounds of Allegheny Observatory, he built a very large whirling table to conduct his experiments. The table had two 30-foot-long spinning arms that could move up to 70 mph. He used it to test the properties of rigid plane surfaces, and designed recording instruments to capture data about their behavior in flight. The experiments eventually led him to make the first successful unmanned mechanical flight (1896) on the Potomac using steam-powered, heavier-than-air flying machines he called Aerodromes. While he was not successful with his own attempts at manned flight, his efforts paved the way for successful manned flight by the Wright brothers in 1903. In his famous book on the subject, he wrote: “If there prove to be anything of permanent value in these investigations, I desire that they may be remembered in connection with the name of the late William Thaw (a major Allegheny Observatory benefactor), whose generosity provided the principal means for them. I (must) thank the board of direction of the Bache Fund of the National Academy of Sciences for their aid and also the trustees of the Western University of Pennsylvania (i.e., University of Pittsburgh) for their permission to use the means of the (Allegheny) Observatory under their charge in contributing to the same end…”. The Langley Aerodrome Number 6 hangs in Posvar Hall on the University of Pittsburgh campus.

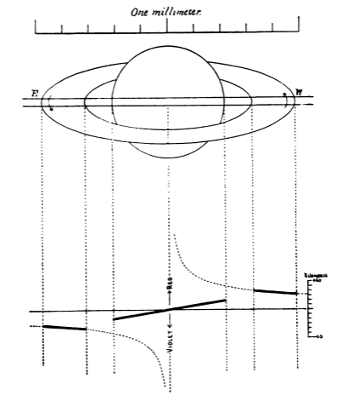

James Keeler was the second Director of the Allegheny Observatory from 1891 to 1898. His spectroscopic study in 1885 revealed that Saturn’s rings are particulate and do not rotate as a solid body. Specifically, he showed that different parts of the rings reflect light with different Doppler shifts due to their different rates of orbit around Saturn. This provided confirmation that supported James Clerk Maxwell’s 1859 calculation which indicated that tidal forces necessitate rings comprised of disconnected particles which must orbit Saturn at their own rate. Keeler made his observations with a spectroscope (built in Brashear’s shop, see below) attached to the 13-inch Fitz-Clark Refractor (Figures 9 and 10). The observations launched the detailed study of Saturn’s rings, which today yield insights into less accessible disk systems. The second major gap in Saturn’s A ring, discovered by NASA’s Voyager spacecraft, was named the Keeler Gap in his honor. Along with George Hale, Keeler founded and edited the Astrophysical Journal in 1895. Keeler (1857-1900) died young, and his cremated remains lie in the Allegheny Observatory crypt underneath the Keeler Telescope Dome. The dome originally housed the 31-inch Keeler Reflector, but today the Keeler Telescope is a PlaneWave 24-inch Reflector, which can be operated remotely.

John Brashear was Director of the Allegheny Observatory from 1898 to 1900. He also served as Allegheny Observatory Committee Chairman from 1893 to 1920 and Chancellor of the University of Pittsburgh from 1901 to 1904. Coming from humble beginnings as a millwright, he became a self-taught gifted optician and mechanical engineer. He made many high-quality optics and precision instruments at his Allegheny Observatory affiliated shop. He developed an improved slivering method, which would later become the standard for coating first-surface mirrors, known as the "Brashear Process," until vacuum metalizing began replacing it in 1932. His instruments gained worldwide respect. Optical elements and instruments of precision produced by John Brashear were purchased for their quality by almost every important observatory in the world. It’s especially notable that Brashear made the optics for the famous 1887 Michelson-Morley interferometer (Figure 11), demonstrating the constant speed of light regardless of motion direction. The accuracy of the Michelson-Morley experiment relied heavily on the quality of the mirrors used to reflect light beams, and Brashear's expertise in this area contributed significantly to the success of the experiment. This was a watershed moment in physics history, refuting the existence of the hypothetical luminiferous ether and leading to Einstein’s theory of special relativity.

The successes prior to 1900, which were largely made possible by the funding of William Thaw Sr., led to enthusiasm for constructing a New Allegheny Observatory building located in Pittsburgh’s Riverview Park on 207 acres, which is less than 5 miles from Pittsburgh’s Golden Triangle. Brashear arranged financing for the new three-domed building, which began construction in 1900 and was dedicated in 1912 at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society. Brashear made the impressive 47-foot long 30-inch Thaw Refractor shown in Figure 4 for the new building shown in Figure 2. The original 13-inch Fitz Clark Refractor shown in Figure 3 was moved into the new building. Brashear also made a 31-inch Reflector, designated the Keeler Memorial Telescope, for the new building. The new Observatory was planned and designed by Brashear and Frank Wadsworth, who was Director from 1900 to 1905, with architect Thorsten E. Billquist. Its architectural style is neoclassical.

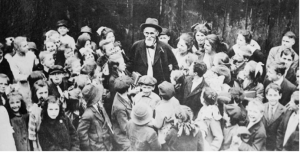

In addition to Keeler’s ashes, Brashear’s ashes are interred, along with those of his wife Phoebe, in the crypt below the Keeler Dome. A plaque on the crypt reads: “We have loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the night,” which is a paraphrase of the last line of the poem “The Old Astronomer to his Pupil” by Sarah Williams. Because of his astronomy outreach to all, John Brashear was admired and beloved by fellow western Pennsylvanians and international astronomers, who familiarly called him "Uncle John".

The Rotunda of the Allegheny Observatory with the bronze statue of John Brashear made by sculptor E. Victor. Also seen is the original, blue-corrected achromatic lens made by Brashear for photographic astrometry with the 30-inch Thaw Refractor. This lens was replaced in the 1985 with a red-corrected lens when red-sensitive CCDs became the preferred detectors for imaging. On the right is the magnificent stained-glass artwork of the Greek astronomy muse Urania by Mary Tillinghast, which was installed in 1903.

Early-1900s Contributions

Frank Schlesinger was the Allegheny Observatory Director from 1905 to 1920 when research in the new building began. Schlesinger pioneered the use of photographic methods with the long-focus Thaw Refractor, with the aim of making a permanent record of stellar positions to measure parallaxes (Figure 14).This provided direct determinations of stellar distances. Over 110,000 exposures on glass plates are housed at AO. It is the most successful photographic, ground-based parallax telescope in the world, establishing the most-accurate distance scale for the local Universe in the early 20th century.

Heber Curtis was the Allegheny Observatory Director from 1920 to 1930. Curtis was famously involved in the so-called Curtis-Shapely Great Debate that took place at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in 1920. Both participants were incorrect about certain aspects of their proposed models for the location of the Sun and the scale of the Universe. But years after the public debate, it became clear that Curtis was correct in his assertion that other galaxies existed beyond our own Galaxy, as demonstrated by Edwin Hubble and others.

Mid-to-Late-1900s and Post-2000 Contributions

After Heber Curtis, the directors were: Frank Jordan (1930 - 1941), Kevin Burns (1941), Nicholas Wagman (1941 - 1970), Joost Kiewiet de Jonge (1970 - 1977), George Gatewood (1977 - 2008), and David Turnshek (2008 - present). All except Turnshek used Allegheny Observatory for their research.

The photographic parallax program concluded in 1985, when Gatewood began parallax measurements with electronic detectors until 2009. Turnshek primarily promotes the use of Allegheny Observatory for Education and Public Outreach. Lou Coban oversees the daily operations. During the academic term, classes meet two nights per week; student or public tours happen three nights a week; public lectures happen on Friday evening once per month; and since 2023 Kerry Handron, a newly hired outreach and events coordinator, has begun offering many opportunities for K-12 students. Recently she arranged for a NASA Moon Tree to be planted on the Observatory grounds. University of Pittsburgh students in classes use the telescopes for fast imaging, photometry, transmission grating spectroscopy, and astrophotography. This includes a program to verify and time exoplanet transits with the 24-inch PlaneWave Keeler Telescope. Some advanced high school students also become proficient with using this telescope for projects that introduce them to research.

With the advent of large telescopes on mountains and space telescopes, the utility of Allegheny Observatory for forefront research faded along with other great observatories built near cities. However, the early impact of Allegheny Observatory is undeniable. It continues to inspire those who visit it.